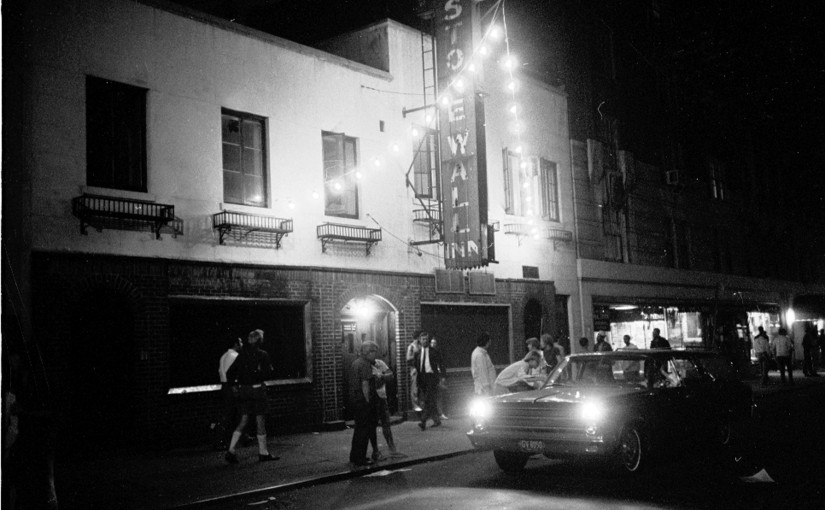

June 28, 1969

I’m not particularly fond of crowded places. Therefore, even if I had been more than two years old at the time and living in New York City, I probably wouldn’t have been at the dive bar run by the Genovese family on Christopher Street early that Saturday morning. Besides, I’m not especially fond of dancing, cheap booze and filthy restrooms, either individually or in combination. Plus, I don’t care for trouble, and this joint always had more than its fair share.

Like many mafia-owned establishments, bootleg (untaxed) liquor was the norm, and police raids were common. Complicating matters, it was illegal to sell liquor to “sexual deviants” or to permit same sex dancing. This particular club was a magnet for the gay and transgender communities. Often the management would be tipped off that a raid was imminent, allowing time for them to hide contraband and/or empty the bar. Barring this, however, typical roadmap of a raid involved seizing the booze and lining up the patrons for ID checks. A female officer would take all those dressed as women into the bathroom and check their genitals. Anyone found to be crossdressed could be arrested. Women could also be arrested if they were not found to be wearing at least 3 articles of feminine clothing. By targeting transgender people (“butch” lesbians, transsexuals and drag queens)–a small minority of the clients–police selectively harassed the most marginalized of the marginalized.

Why things didn’t go as planned that evening isn’t entirely clear. Maybe everyone was still sore about a raid on the previous Tuesday. The relationship between the bar and clientele wasn’t exactly rosy either–apparently the mafia owners had been blackmailing wealthier clients by threatening to out them to their employers. Additionally, New York police vice squads were arresting about 1000 homosexuals per week. Those arrested would be publicly exposed and stand to lose their jobs.1 Undoubtedly, by 1:00 AM a prodigious amount of liquor had been consumed. A perfect storm was brewing fueled by chronic oppression, long-held resentments and a gathering mass of intoxicated people who felt that they had nothing left to lose.

Police entered the bar, turned on the lights, stopped the music and barred the doors. All of this had happened before, but on this particular night, many of the men refused to show ID. Lesbians and transgender clients refused examination. Police persisted, handcuffing some and shoving others. Some of the women were felt up by officers “looking for evidence.”2 Those released did not disperse. Squad cars attracted more attention to the scene and the gathering swelled to 500 or more. When police roughly escorted one handcuffed woman out of the bar, the burgeoning crowd erupted.

The riots which ensued on that night are now remembered by the name of the bar where the spark ignited–the Stonewall Inn. They were not the beginning of the fight for LGBT rights, but rather a memorable rallying point, a defining moment which signaled the growing refusal to accept an unacceptable status quo and the authority attempting to enforce it. LGBT activists still speak of civil rights pre-and post-Stonewall in much the same fashion as others speak of civil rights post-Selma or more recently, post-Ferguson. One year later, on June 28, 1970, a galvanized LGBT community marked remembrance of the riots with simultaneous marches in New York, Los Angeles and Chicago. These marches recurred annually and proliferated to cities across the country. Pride was born.

Those of you who were among the 500,000+ who ventured downtown for Twin Cities Pride a couple of weeks ago would be hard-pressed to recognize that the rainbow-soaked, corporate-sponsored fiesta in Loring Park owed its existence to one summer night decades ago when a frustrated minority turned violently against the establishment which was oppressing them. These days, city police parade in celebration of Pride. Along with them march senators and mayors, businesses and churches.

Like many of you, I knew little to nothing about Stonewall before I made my first pilgrimage to Twin Cities Pride. All I knew at the time was that pride was the very last thing I felt about myself. I hoped that a day among people who celebrate the vivid spectrum of human experience would be tonic against the shame which was my daily burden. Happily, this proved to be the case.

2015 marks my seventh Twin Cities Pride. It’s probably the closest thing to a high holy day in my book, and the fact that Kathy joined me for the first time this year made it 53% Pride-ier. You can, if you look, still find undercurrents of protest and admonishments to tackle unfinished business, but mostly it’s a festival as festivals go–deep fried, sun-baked, garish, boisterous, corporate, shoulder to shoulder and generally over-served. Face paint and port-a-potties. Balloons and beer tents. Dachshunds in tutus. Epically rainbow.

On any given day, I prefer the serenity of my rural hilltop to the buzzing electricity of downtown. So, although you wouldn’t have found me at the Stonewall in the summer of ’69, you can be sure that I will be somewhere lost in the crowd for its annual remembrance. See you next year.

- In 2015, it is still legal to fire people for being LGBT in 29 states. Marriage equality is not the end of the struggle.

- Been there, done that. Before I changed my legal name and travel documents, I was routinely scrutinized by airport security and subjected to numerous pat downs. One female officer in Amsterdam clearly crossed the same line as those cops in 1969, feeling for more than just hidden weapons.